Words: Ed Smith

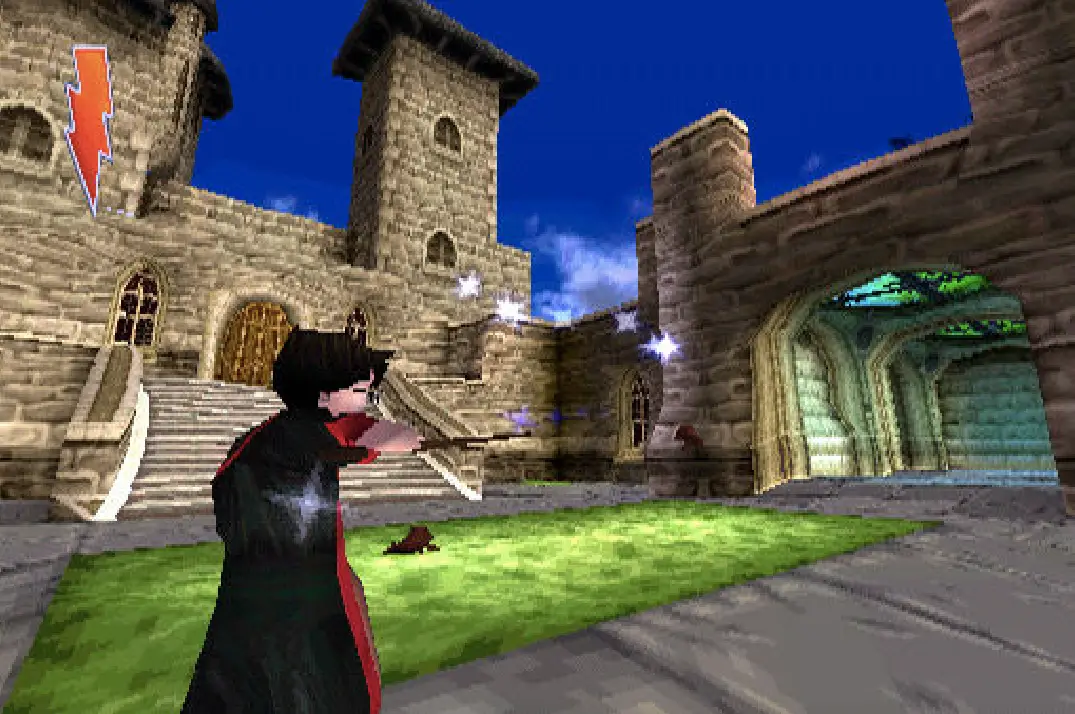

The Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone PlayStation 1 game. It surprises me how often I think about it. I don't know much about Harry Potter. I don't especially like Harry Potter. But that game, even though it's now 21 years old and, if you check on Wikipedia, received pretty lukewarm reviews when it was released, somehow it still lives on in my head. "What are you writing about?" asks my wife, who never, ever plays video games. "There was this Harry Potter game for the PS1..." "Oh!" she interrupts. "I LOVED that game!" Clearly, this game has something about it. There is something about this game, if you'll pardon the pun, that is truly magical.

And I think I know what it is. I think it's Hogwarts. But not Hogwarts as described by J.K. Rowling - Hogwarts as it was rendered on the PS1; Hogwarts as was created by the now-defunct UK studio Argonaut Games. (Their founder was a guy called Jez San - Jez San and the Argonauts, get it?)

Take yourself back to 2001 by watching the trailer for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone on PS1...

Open-world games, of a style that we could recognise now as distinctly "open-world" (you freely explore a city, town or landscape; there are several optional mission strands; as you progress, you earn points or currency which you can decide how to use to upgrade your character) were seriously beginning to find their feet in 2001. RPG series like Diablo, Elder Scrolls and Final Fantasy had established the rules. Shenmue, Headhunter and of course Grand Theft Auto III, which released just a month prior to the PS1 Potter in October 2001, shook up the formula. There was a push towards different kinds of environments. The worlds of sandbox games became more familiar, more believable, more recognisable from real life.

It's a matter of technology, of course. But at the same time, even games set in universes that are purely fantastical, where the overall aesthetic is dragons, spells and whatever, you can see a move in terms of level design and space away from very identifiable video game geometry to something more plausible and lived in: the dungeons in Ocarina of Time have these very convenient polygonal platforms for you to jump onto and seem like they couldn't serve any other purpose than as a video game level, whereas the world of Breath of the Wild looks and feels like somewhere people might actually live and function. What's interesting about Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone is how it seemingly exists at the precise moment where one open-world level design discipline was transitioning to another - the Hogwarts of this game is very "video-gamey", but at the same time feels inhabited and alive, somewhere closer to real.

A few details that stand out. First of all, the sheer size of the thing. From the very start of the game you're free to walk around Hogwarts and as you explore, through the libraries, the dorms and the Great Hall, you'll come across almost every Slytherin, Hufflepuff and house ghost that you might remember from the books. That in itself isn't exceptional - this was a franchise tie-in game: they were bound to drop in every single character they could, to strengthen the appeal - but it's the way that they're used.

You see Hogwarts students running back and forth along the corridors trying to get to class. The ghosts spring suddenly from the walls, float across the room then vanish again in front of you. It's nothing compared to what you would get now (just watch some of the trailers for Hogwarts Legacy) but at the time, and if we're trying to trace the sort of ancestry of the lived-in open world, details like these created a sense that there was something going on around you, that this was a world you inhabited but didn't entirely control.

This feeling, that things are happening beyond your field of view, regardless of your actions as a player, is fundamental to making a game world feel alive. It's what we recognise as real. If the world around us only moved in response to our moving, and everything in it seemed designed towards us as players then it wouldn't be the world, it'd be The Truman Show.

One other detail, even more minor. We take the kind of GPS/line-on-a-map telling you where to go function in open-world games for granted now, but I remember when GTA: San Andreas came out, there was a big deal made about the fact that finally you could set yourself waypoints to stop yourself getting lost. What this also added was a sense that CJ knew Los Santos - it was where he was from, it was where he grew up, so driving around looking for Burger Shot or Reece's barbers wouldn't have made sense; those little waypoints added to the cogency of the character. In The Philosopher's Stone, whenever you approach a door or the entrance to a hallway, a little heading appears telling you where it leads. Before you go inside and trigger a loading screen, you can see that, for example, this door goes to the Gryffindor common room or the potions lab. It's a small detail, but in terms of creating that sense that this is a real place and that you live here and you're part of it - that you're immersed in it; that magic - it goes a long way.

Particularly in the 1990s, video game levels were designed to be deliberately impassable and obfuscated. The world was meant to present a kind of geographical challenge that you had to work out and overcome. The Hogwarts of The Philosopher's Stone felt more like something, or somewhere, that you were supposed to just enjoy and indulge in, somewhere you could roam without fear of getting stuck. It's telling that when Argonaut Games closed down in 2004, many of its members went on to form Rocksteady. The same sense of a real, lived-in place, with negotiable geography, that is implied to exist as something more than just a video game level, permeates especially Batman: Arkham Asylum's titular penitentiary, one of the most impressive game locations of all time for the way it fits together and feels believable.

Likewise, if you scour the credits of the game's PC version, you will find Jordan Thomas, the level designer who would go on to create the Shalebridge Cradle from Thief: Deadly Shadows and BioShock's legendary Fort Frolic, where you encounter the psychopathic artist and musician Sander Cohen. All of these levels achieve a subtle combination, where you are encouraged to explore and treat the world like a sandbox, but where that exploration is couched in a sense of plausibility and cohesion - an implication that the world does not just exist for you, the player. At the time in 2001 but even more so when you look back at it and trace its influences and descendants, that, I think, is what makes Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone feel magical.

Follow the author on Twitter at @esmithwriter.

Featured Image Credit: EA, Argonaut GamesTopics: Harry Potter, PlayStation, Retro Gaming